The adoption of AI in journalism has been characterised by a hype cycle that often exaggerates its potential, fuelled by sometimes aggressive marketing and misconceptions. Despite fears of human replacement, AI remains a complementary tool rather than a replacement, and its true value lies in supporting human creativity and decision-making.

Up to the end of November 2022, the launch date of ChatGPT, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have been used in the media mainly for four key applications:

- Automated text generation from structured data: This data-to-text model requires high-quality data and is mainly used in areas with strict data quality requirements, such as sports, elections, finance or the environment.

- News recommendation and personalisation: These systems use readers’ data to enhance their experience by offering content tailored to their interests and behaviours.

- Analysing large data sets using machine learning: This includes applications such as content classification and categorisation, trend prediction and text data analysis using natural language processing (NLP) techniques.

- Assist with repetitive and time-consuming journalistic tasks: AI is used to monitor real-time events on the web and social media to quickly identify key information and assist with verification processes.

These different types of activities are grounded in data-driven journalism, which is not a new phenomenon. However, it has become more attractive for two main reasons: the computerisation of practices due to the increased availability of data, and the increase in computing power. This means that professionals involved in these different practices need to have more or less significant human resources, specialised skills and financial means. For this reason, practices based on AI technologies have often been limited to well-defined contexts and aimed at meeting specific needs: extending media coverage, satisfying the need for immediacy, exploring strategies for audience loyalty and engagement, assisting journalists with particularly time-consuming tasks.

The ethical debate focused mainly on the use of automatic text generation and calibrated distribution information, and on the need to inform the public about the technologies and systems used. In Europe, only two press councils had published recommendations on the subject. In the academic world, ethical reflection was present but concerned a number of limited studies. In professional circles, on the other hand, the metaphor of the robot journalist made fear a major substitute. We needed to wait for the advent of generative AI to relaunch these debates, without however essentially considering the very heart of what constitutes AI technologies: data.

AI without knowing it

Journalists have gradually integrated AI technologies into their daily practices, without much consideration of the nature of the technologies underlying these applications, such as spell-checking, online search, social media monitoring, or even automatic transcription and translation. These practices, now generalised, have been integrated almost naturally into journalistic routines, without raising major questions about their ethics or practices.

Does 30 November 2022 mark the end of the era of pre-generative AI in media information? Yes and no. The real breakthrough would be in providing access to functions previously reserved for IT and data professionals. No specific skills are needed to manipulate generative AI: a simple instruction, a prompt on a screen, is now enough to interact with these technologies. This is why AI has generated real enthusiasm in journalistic circles: AI accessible to all, capable of performing tasks quickly and impressively. The technology is so impressive that it has rekindled fears of the Great Replacement and raised the question of the added-value of the human journalist.

Large language models such as ChatGPT are prone to error due to major quality issues in their training data and a tendency to produce hallucinations that refer to content that is not ground truth. Therefore, these tools are more likely to be used for secondary tasks that do not directly affect the quality of information in the sense that they need to be controlled. Also, the verification phase remains largely human-driven due to concerns about trustworthiness and ethical considerations. Moreover, the use of such technologies for the most creative tasks of journalism – generating ideas for stories and angles – raises the question of possible de-skilling. Isn’t it said that a well-sharpened mind requires a well-trained mind? Yet dominant discourses often tend towards enthusiastic utopianism: generative AI is hailed as the long-awaited revolution in journalism, promising to economically transform professional practices and models. But let’s be realistic: what can these AIs do that existing technologies cannot? What specific needs will they address? What exactly will they change? Are we not, in fact, caught up in a widespread trend that exaggerates the potential of AI beyond what it really is?

Between the ideals and the realities on the ground

The AI Journalism programme offers a clearer understanding of the real penetration of AI technologies in the media landscape. Led by the London School of Economics (LSE), this programme aims to promote the development of responsible technologies within newsrooms. On its website, it features a database listing 156 AI-based journalistic projects developed over a period of seven years. The majority of these projects focus on the production and distribution of information, with nearly 10% specifically dedicated to generative AI and synthetic media.

These data show that the use of AI is part of a number of well-defined strategies, even if the overall volume is not as widespread as might be expected on a global scale, although we also recognise that these data are not exhaustive. This suggests that AI technologies are being used to address specific needs, such as information gathering, verification, investigation and audience segmentation. Forty percent of these projects are related to European media or journalistic initiatives, with the majority coming from the UK and, to a lesser extent, Germany. Notably, none of these projects involve Belgium or its neighbouring countries.

Research on the integration of AI and generative AI technologies into fact- checking practices in the Nordic countries – known for their openness to new technologies – has shown that professionals do not perceive AI as an end in itself, but rather as a means, a tool that cannot replace skills, cognitive, complex human tasks such as analysis, context or critical decision-making. Some fact-checkers have reported their scepticism, lack of trust and inability to find a suitable space for the use of generative AI.

Overall, there is limited confidence in the results provided by GAI tools. These technologies are also perceived as posing several challenges that are difficult to address in fact-checking, mainly because of the reliability issues associated with GAI systems, either in terms of training data or artificial hallucinations, which can result in causing confusion or reducing trust—“We will create a lot of additional work for ourselves just going through the possible hallucinations, checking all the sources and so on” (FC_06_2).

The AI hype cycle

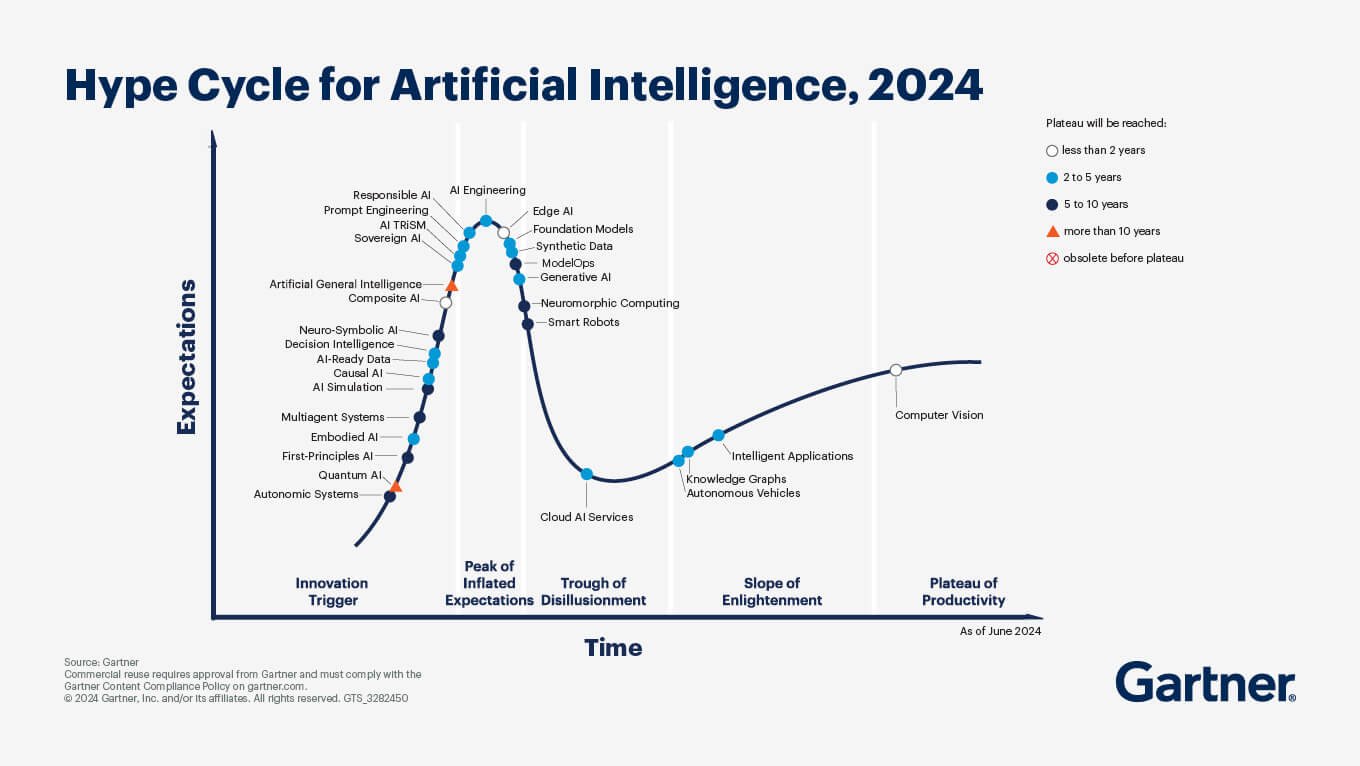

Beyond the realities on the ground, it is important to critically examine the phenomenon of technology hype, which can be defined as the exaggerated media and commercial presentation of a technology’s potential, often driven by enthusiastic rhetoric that presents an idealised view of its impact. The concept of the hype cycle was introduced by the American consulting firm Gartner. This model illustrates the progression of emerging technologies through five distinct phases, reflecting their maturity, adoption and societal application.

- Technology trigger: This early stage is characterised by a technological breakthrough or innovation that attracts media and investor attention, generating excitement and speculation about its potential.

- Peak of inflated expectations: At this stage, enthusiasm is at its highest, but expectations often become unrealistic. The technology’s promises are exaggerated, leading to excessive hype, while its true capabilities fall far short of the collective imagination.

- The trough of disillusionment: As early experiments fail to live up to expectations, the technology enters a period of disillusionment. Its limitations become more apparent and adoption slows. Some may abandon it, while others seek ways to overcome its challenges.

- Slope of enlightenment: After overcoming initial setbacks, the technology begins to mature. Practical solutions and concrete use cases emerge and adoption begins to stabilise. Initial promises are adjusted to reality and interest in the technology is rekindled.

- Plateau of productivity: The technology is fully integrated into practical applications, with growing adoption and tangible use across different sectors. It reaches maturity, where its benefits are clearly understood and it begins to deliver measurable returns on investment.

Between marketing strategies and journalistic discourse

The hype cycle is a clear illustration of how emerging technologies go through periods of over-exuberance and disappointment before finding their true place in practice. By observing this dynamic, we can pinpoint the space between the peak of inflated expectations and the trough of disillusionment. However, it is quite possible that the slope of enlightenment will take time to materialise. OpenAI, for example, recently announced that version 5 of its GPT is not yet ready because it has not achieved the expected level of efficiency, despite significant costs – an estimated $500 million for just six months of training. According to Fortune, the generative AI market attracted nearly $44 billion in investment by 2023. Given these costs, it’s understandable that companies working in the field, along with their shareholders, are eager to convince others of the inevitability of their technology, often exaggerating its potential and performance while overlooking its limitations, including hallucinations and biases.

The hype is also fuelled by sometimes aggressive marketing strategies and a growing number of brand new AI experts and futurists who often seem reluctant to put their pink glasses on their keyboards. But they are not the only ones to blame; journalists also have their fair share of responsibility. By over-personalising AI technologies (« AI knows », « AI thinks », « AI doesn’t want », « AI doesn’t like », etc.), they ascribe to them human-like qualities that these technologies are far from possessing – such as creativity, general intelligence and empathy. In journalism, AI is sometimes used too broadly or inaccurately to describe any advanced technology, whether or not it is actually based on artificial intelligence. This contributes to confusion and the spread of misconceptions about what AI is, similar to how many companies claim to use AI in their products when they do not. There is also a growing fear of being left behind, leading to a rush to adopt these technologies without fully considering their real implications.

The good news is that, despite the inflated rhetoric around generative AI technologies and their supposed ability to replace human journalists, it is unlikely that an army of software will take over media content any time soon – at least not when it comes to producing high-quality information. A clear example of this is the ‘robot’ that once replaced a journalist but has now been fired. Meanwhile, the idea that AI is more of a bubble than a gold rush is gaining traction in some public discussions, and this bubble may have already started to deflate.

“Journalism caught in the AI hype?” – A conference-debate organised by FARI, the AI Centre for Responsible AI at ULB and VUB, on January 27 in Brussels. Information and registration by following this link.