Keynote presented at the National Conference of Journalism Professions (CNJM), organised at the journalism school of Tours, on January 29, 2026.

1.

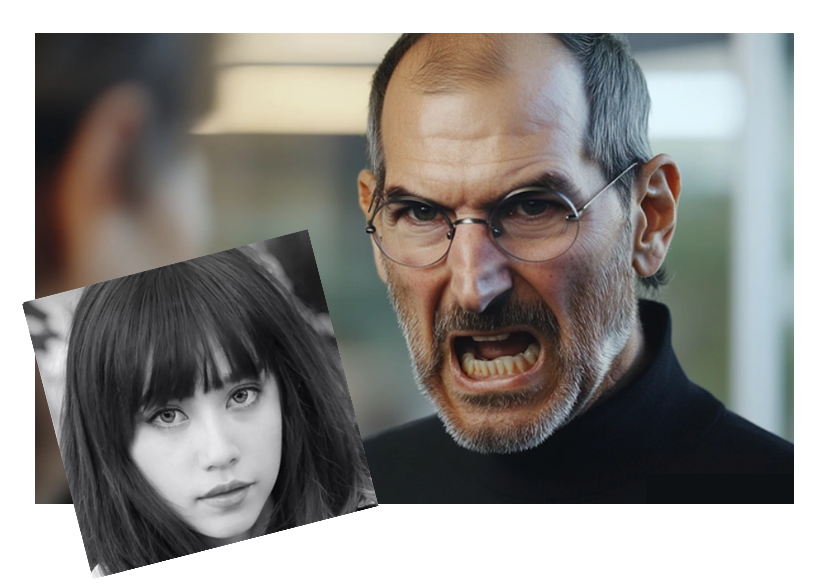

The two images referenced above illustrate the potential risks of generative artificial intelligence in the media. The woman depicted is a fictional journalist whose articles were produced by a language model for a prominent women’s magazine. Conversely, the man shown is deceased, and the image itself is entirely artificial, generated solely to accompany an article.

Since the launch of ChatGPT slightly more than three years ago, journalism ethics has become a prominent subject of debate. Artificial intelligence has been present in the media for some time, eliciting both apprehension and optimism. The current shift lies in the increased power and availability of generative tools, which can produce text, images, audio, and video within seconds. These concerns are heightened by the fact that such tools are now frequently used to create and amplify disinformation.

The distinction between fact and fiction is increasingly ambiguous, challenging established relationships to facts and professional standards. These developments disrupt journalism practices and prompt a fundamental question: Is journalism’s ethics at risk?

2.

Journalism ethics has always been under pressure. In 2009, Daniel Cornu raised the central question of the relationship between journalism and truth. He emphasised that journalism traditionally claims to uphold the truth, but that this claim is weakened by numerous criticisms: media errors, manipulation, economic and political pressures, and growing public distrust. Between the ideal of truth to which journalists aspire and the concrete conditions of information production, a structural gap persists today. The search for truth appears less as a fully achievable goal than as a normative horizon, constantly tested by the realities on the ground.

In 2016, in his journalism ethics manual, Benoît Grevisse addressed the ethics and deontology of journalism not as strict rules, but as reflective and professional principles that are part of the daily production of information. Ethics is a space of permanent questioning, within which journalists are led to arbitrate between professional values, such as truth, independence, and social responsibility, and organisational, economic, and symbolic constraints.

Cornu and Grevisse demonstrate, each in their own way, that journalism ethics is neither a proclamation of principles nor a formal adherence to rules. It is built through action, through situated choices, often imperfect, but essential for preserving the credibility and legitimacy of information in the public sphere.

3.

The integration of AI in newsrooms does not fundamentally alter the main ethical principles. Truth, responsibility, independence, and credibility remain central, yet AI shifts public and professional debate toward technology, sometimes overshadowing lasting, unresolved issues. The use of AI accelerates content creation, expands available formats, and further obscures the distinction between news and fiction, thereby increasing the risks of disinformation, sensationalism, and diminished accountability.

While generative AI is widely discussed, AI in media encompasses predictive systems, automation tools, and recommendation algorithms that assist news production and dissemination. These distinctions are important because different AI types, such as generative AI, predictive systems, and recommendation algorithms, each raise distinct ethical questions.

4.

This relates, more broadly, to the need to develop AI education, also known as AI literacy. From this perspective, understanding artificial intelligence is like unpacking layers, each revealing additional complexity.

The initial layer pertains to technical and conceptual competencies. This includes understanding the operational mechanisms of these systems, their capabilities, and their limitations. Without this foundational knowledge, it is not possible to accurately assess risks or determine appropriate applications.

The second layer concerns critical and ethical skills. It is not enough to know how an algorithm or a large language model works; one must also examine their professional impacts. How do these technologies influence information production, transparency, or accountability? What biases do they introduce, and how do they affect audiences?

The third layer involves practical skills, including the development of responsible and considered practices for content production and dissemination. This also requires the ability to reject inappropriate uses, implement safeguards, and integrate ethical considerations within daily decision-making. Journalists should commit to ongoing ethical education and consistently challenge questionable practices.

5.

AI literacy helps dispel major misconceptions, particularly the idea that large language models function like databases or that they understand language the same way humans do. In reality, they are probabilistic systems that generate statistically consistent responses. While this implies complex architecture and massive datasets, these models lack consciousness and semantic understanding. They simply produce calculated correlations. This understanding of major language models was virtually absent at the time of ChatGPT’s launch, which is probably what sparked a wave of enthusiasm, fueled by sometimes excessive rhetoric that presented AI either as a saving grace for the media or as an existential threat to journalism.

AI literacy enables a critical examination of techno-solutionist narratives and supports a deeper understanding of the limitations and challenges associated with individual technology use. It also clarifies how AI technologies can provide value when responsibly integrated into professional contexts. In Norway, for example, the Demokratibasen project aims to use artificial intelligence to make public documents more accessible and facilitate the work of local journalists. The tool offers features such as automated analysis, text summaries, and content prioritisation based on journalistic relevance, helping newsrooms save time and improve their local news coverage.

6.

It is important to recognise that the technological framework frequently surpasses the technical expertise available to journalists. Frequently overlooked is that, in some newsrooms, machine learning and data specialists contribute to editorial workflows by developing tools, algorithms, and automated systems. However, their input is often disregarded or insufficiently incorporated into ethical deliberations.

Journalism and computer science represent professions with distinct epistemologies, where key concepts may hold different meanings. For instance, terms such as accuracy, objectivity, and transparency are interpreted differently across these fields. This divergence underscores the need to nurture interdisciplinary collaboration to guarantee that journalistic ethics adequately address the implications of AI technologies.

7.

We often talk about the relevance of integrating journalism values directly into artificial intelligence systems, as if these values could be translated into technical rules or programmatic parameters. However, this idea rests on a largely simplistic view of how AI models, particularly large language models, function. These systems possess neither intentions nor normative judgment: they cannot arbitrate between public interest and sensationalism, nor can they assess the social relevance of information.

Attributing objectivity, responsibility, or ethics to statistical models mistakenly projects human capacities onto systems that perform probabilistic calculations. Rather than seeking to moralise algorithms, the challenge is to build sociotechnical systems in which AI serves as a tool subordinate to clearly defined professional standards. It is imperative that journalists, technologists, and stakeholders establish governance structures and oversight processes to ensure that these standards are rigorously upheld in practice.

8.

In their daily work, journalists use artificial intelligence technologies, often without fully realising it, whether by spell checkers, transcription tools, or translation software. These seemingly innocuous uses nevertheless present ethical challenges that are rarely questioned, such as respect for confidentiality, the accuracy of the content produced, and the unintentional influence on the wording and meaning of information.

With the rise of large language models, a new trend is emerging: augmented search engines that are no longer queried by keywords but by questions, in a new paradigm of human-machine interaction. It is now imperative that journalists proactively engage with and question these technologies to guarantee they align with professional standards and ethical values. These new « epistemic » agents now deliver answers as summaries rather than just lists of links. Like large language models, they neither verify the authenticity of sources nor distinguish between truth and falsehood, raising new questions about trust and human authority.

Whether we think of Google’s AI assistant or the Perplexity search engine, these systems entail the same epistemic problems as the language models from which they derive: hallucinations, semantic noise, the reproduction of cultural and social biases, and the risk of manipulated content. In the same way that they can produce misinformation, that is, incorrect content generated without intent to deceive and directly linked to the probabilistic mechanisms of the models, these technologies can also be instrumentalised to spread disinformation, which stems from an intentional desire to manipulate audiences.

9.

It is also important to remember that generative AI is not neutral. Behind it are technology companies whose design and deployment choices often respond to commercial, strategic, or even ideological considerations. These choices directly influence the data used to train the models, the optimisation parameters selected, the types of content prioritised, and the integrated filtering and security mechanisms. In other words, the systems we use bear the imprint of the values, priorities, and trade-offs made by the actors who develop them.

Generative AI also makes promises that are not always fulfilled. In the United States, studies from MIT, among others, have shown that the use of generative AI in the private sector often encounters limitations, with a small proportion of pilot projects generating a significant financial impact. Furthermore, the proliferation of « AI slop » or « workslop, » which refers to low-quality content produced by AI, increases the workload of employees who must sort, verify, and correct it. For journalists, this development often results in an increased workload rather than time savings.

Today, the volume of online content generated by AI exceeds that produced by humans, which naturally raises suspicion: Is this content complete, accurate, and reliable? In this digital environment, the overabundance of information goes hand in hand with misinformation, a phenomenon amplified b social networks, where polarising, emotionally charged content is favoured by the logic of the attention economy.

The increasing speed and volume of unreliable content are reducing the time available for thorough fact-checking, posing a major obstacle to ethical practices. Faced with this dynamic, AI plays a paradoxical role in fact-checking, as it can help identify patterns of disinformation and deceptive narratives. In the ideal hybrid approach, widely adopted by European fact-checking organisations, humans and machines combine their strengths while editorial responsibility remains entirely with journalists.

10.

Journalism ethics, rooted in a duty-based ethic, rests on fundamental principles to ensure the quality and integrity of information. All these principles naturally apply to the use of AI technologies in newsrooms. However, the rise of generative AI has led many media and professional organisations to publish a series of charters, recommendations, and position statements over the past three years. There are at least fifty such public texts in Europe, and some national codes of ethics, such as those in Flanders, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Italy, Serbia, and Slovenia, now include specific sections on AI.

These texts agree on common principles: recognising AI as an integral part of the editorial process, experimenting in a cautious and controlled manner, ensuring transparency by disclosing generated content and specifying the conditions of use, maintaining balance and diversity in the processing of information, and keeping humans in the loop in order to preserve editorial control and responsibility.

However, these charters and recommendations have several limitations. They often remain too general to be applied effectively in the face of rapid technological developments, and certain points, such as the explainability of systems or the practical evaluation of tools, are difficult to implement in the reality of editorial work.

Journalists commonly lack the technical skills to fully participate in the development or auditing of tools, and simple transparency about the use of AI is not enough to correct algorithmic biases, address errors in training data, or prevent the production of results containing elements of misinformation or disinformation.

11.

Like all social norms, ethical norms are always the product of collective bargaining and power relations. Artificial intelligence technologies do not create these norms from scratch. They make them more visible, more explicit, and more reflective.

This is why it is essential to enrich the ethics of duty with ethical reflection based on the consequences of actions. Here, the challenge is no longer simply to comply with rules, but to question the purpose and social impact of using AI technologies in newsrooms. This consequentialist approach, which places the assessment of risks, impacts, and benefits at the heart of moral judgment, aligns with contemporary concerns addressed by instruments such as the AI Act, the European regulatory instrument that promotes shared responsibility in the face of technologies ubiquitous in our lives.

The French press council (CDJM) concretely illustrates this consequentialist approach: its recommendations adopt a risk-based approach toward information quality. It distinguishes between low-risk uses, such as spell-checking, which do not require disclosure; moderate-risk uses, such as machine translation, which require transparency and disclosure; and high-risk uses, which are prohibited because they involve generating content that could mislead audiences.

If we recall the photo of the angry man shown in the introduction, it was an AI-generated image of Steve Jobs, published by the website Jeuxvideo.com to illustrate an article. This illustration, showing the Apple co-founder with his face contorted by anger, led to a complaint being filed with the CDJM (French Digital Media Ethics Committee), which ruled that publishing a « fake » constitutes a major ethical breach, as it does not respect the principle of truthfulness and therefore risks misleading the public.

12.

The use of AI-generated images to illustrate an article is one ethical issue in journalism. Another risk lies in a blind trust in technology, which can lead to insufficient human oversight. Last year, the Norwegian news agency published a story based on a report from a Scandinavian telecommunications company that contained fabricated passages, including the name of a fictitious manager. This incident occurred because a journalist used an AI tool without verifying the generated content, directly violating editorial standards.

However, professional misconduct isn’t always attributable to journalists. In Belgium, the publisher Ventures Media « hired »—if one can even use that term—two journalists for the Dutch- and French-language editions of Elle Belgium. We see here Sophie Vermeulen, a completely fabricated character, credited with over 400 articles published in the three months leading up to the scandal’s revelation in June 2025. Fictitious journalist profiles and generated articles were also used in other magazines belonging to the publisher, including Forbes and Marie Claire. The publisher defended itself, arguing that the tests were temporary editorial tests.

This example demonstrates the risks inherent in a purely utilitarian approach that prioritises efficiency over transparency and integrity. It underscores the necessity for broader editorial responsibility that encompasses not only journalists but also management and executive leadership.

13.

Ultimately, the central issue is one of trust, a resource that has been in decline for several years. The adoption of AI, rather than restoring trust, may exacerbate this divide: while some media organisations view these technologies as a solution to ongoing structural challenges, they may also produce unintended negative consequences.

Research from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University shows that audiences remain sceptical of AI-generated content, doubting its accuracy and reliability. This scepticism varies depending on the type of use: spelling and grammar correction is generally well accepted, while the generation of editorial content meets with much less tolerance, highlighting the importance of maintaining human oversight.

14.

The rules establish essential benchmarks, the analysis of consequences allows us to anticipate risks and social impacts, and the ethics of virtue ensures responsible judgment when existing frameworks prove insufficient or inadequate.

A fully developed ethical reflection cannot do without the third major philosophical tradition of ethics: virtue ethics. This approach shifts the focus from rules and consequences alone to the agent’s moral dispositions.

It invites us to reflect on the professional and human qualities of the journalist that enable them to exercise ethical judgment in complex, uncertain and often unprecedented situations, such as those posed by the integration of AI technologies into editorial workflows. Nevertheless, journalism ethics is not in a worse state today, though it is once again subject to significant challenges. It requires us to reflect on fads, disruptive rhetoric, and all the grand utopias and dystopias surrounding artificial intelligence. This necessary reflective approach once again highlights the critical importance of AI literacy.

Disruption, defined as a fundamental break from established structures and practices, is frequently conflated with the novelty and promotional rhetoric surrounding generative AI. In reality, the most significant disruption arises less from the technology itself than from the unrealistic expectations placed on these tools, which often exceed their actual capabilities. However, the institutional coherence of journalism rests on three pillars: fact-checking, editorial judgment, and the responsibility of authors, and these pillars are not being called into question.

15.

Framing the adoption of AI in journalismas an unavoidable response to contemporary complexity may also represent a form of abdication. AI systems do not interpret content; instead, they structure, filter, and prioritise information according to processes that are neither neutral nor transparent. Rather than critically examining the economic and organisational constraints that hinder quality journalism, there is a risk of passively accepting these limitations.

Moreover, discussions of AI ethics should not obscure the significant crises confronting journalism as a profession, institution, and organisation. While AI technologies may address certain operational challenges, they do not address the profession’s precarious nature. In fact, they may exacerbate these vulnerabilities. Additionally, AI will not remedy structural issues such as media concentration, declining business models, or the erosion of audience trust.

AI can offer tools and operational support, but it does not constitute a solution to the systemic challenges undermining journalism.

Journalism has always faced ethical tensions, calling for a balance between professional ideals and organisational constraints. The increasing use of artificial intelligence technologies in newsrooms, coupled with a shift from an information society to a disinformation society, presents a major double challenge involving technological, social, economic, and epistemic aspects.

These challenges do not call into question the foundations of journalism ethics: the search for truth, independence, and credibility remain central to the profession. However, they call for a rethinking of the role and place of journalism amid a growing blurring of the lines between fiction and reality.

As I concluded in my article published last year in the I2D journal, the intersection of AI and disinformation may present new opportunities to rebuild trust with audiences. Journalists can position themselves as impartial arbiters and reaffirm their role as reliable points of reference amid the prevailing informational uncertainty.

The French original version of this paper was automatically translated with Google Translate and then manually post-edited.