The integration of artificial intelligence into journalism is often framed as a question of technological capability – what AI can do. But a more pressing question is: what do journalists actually need? This is not always easy to determine, as needs are often implicit, shaped by professional practices, workflows and constraints, rather than explicitly stated. These notes were inspired by participation in a research and innovation workshop on « Responsible AI, public service journalism and user needs », at the invitation of Laval University in London today.

Journalists rarely articulate their needs for AI tools in clear, technical terms. Instead, their needs emerge from day-to-day struggles: the pressure of real-time reporting, the challenge of verifying information quickly, and the demand for accuracy in an era of misinformation. Often, they only recognise a need when a gap in their workflow becomes impossible to ignore – for example, the lack of a real-time social media monitoring tool or automated fact-checking support.

Understanding these needs requires looking beyond direct user feedback. It means observing how journalists work, analysing their interactions with existing tools and identifying barriers to adoption. In other words, understanding needs means understanding uses.

A purely technological approach – developing AI based on stated user needs – risks overlooking deeper professional and cultural factors that influence adoption. My research into the needs of journalists as end-users of technology, which began with my PhD, suggests that implicit needs can be uncovered through:

- Examining newsroom workflows and decision-making processes

- Identifying moments when journalists struggle with inefficiencies

- Exploring professional values that influence tool acceptance (e.g. trust, editorial control, accuracy)

This socio-technical perspective helps explain why AI adoption is often uneven. Resistance isn’t just about scepticism about technology – it’s also about organisational structures, newsroom cultures and ethical concerns.

My first case studies of two Belgian newsrooms highlight the complexity of AI adoption in journalism. The study focused on the use of AI-driven automation to cover topics such as air pollution in Brussels and the stock market. It found significant resistance among journalists, driven by concerns about job security, a lack of technical understanding and scepticism about management-led technological change. Many saw AI as a potential threat to their professional identity rather than a supportive tool. However, adoption was more successful when journalists were directly involved in the design process, when AI tools adhered to journalistic standards, and when trust was built between journalists and developers. This reinforces the idea that successful AI integration requires more than just technical efficiency – it requires consideration of professional values, newsroom culture and the everyday realities of journalistic work.

In another study with Pr. Carl-Gustav Lindén at the University of Bergen, we explored the needs of 18 fact-checkers and managers in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Norway and Sweden to understand how AI could better support fact-checking workflows. Using human-computer interaction (HCI) principles, the study explored not only the functionality of AI tools, but also the cognitive, emotional and ethical factors influencing their adoption. The findings highlighted several key barriers: a lack of awareness of existing AI tools, the time required to master them, and concerns about technical complexity. Fact-checkers emphasised the need for AI solutions that align with journalistic values, such as accuracy, transparency and adaptability to different contexts. The study reinforced the idea that successful adoption of AI in fact-checking depends not only on technological advances, but also on trust, usability and ethical integration into journalistic practices.

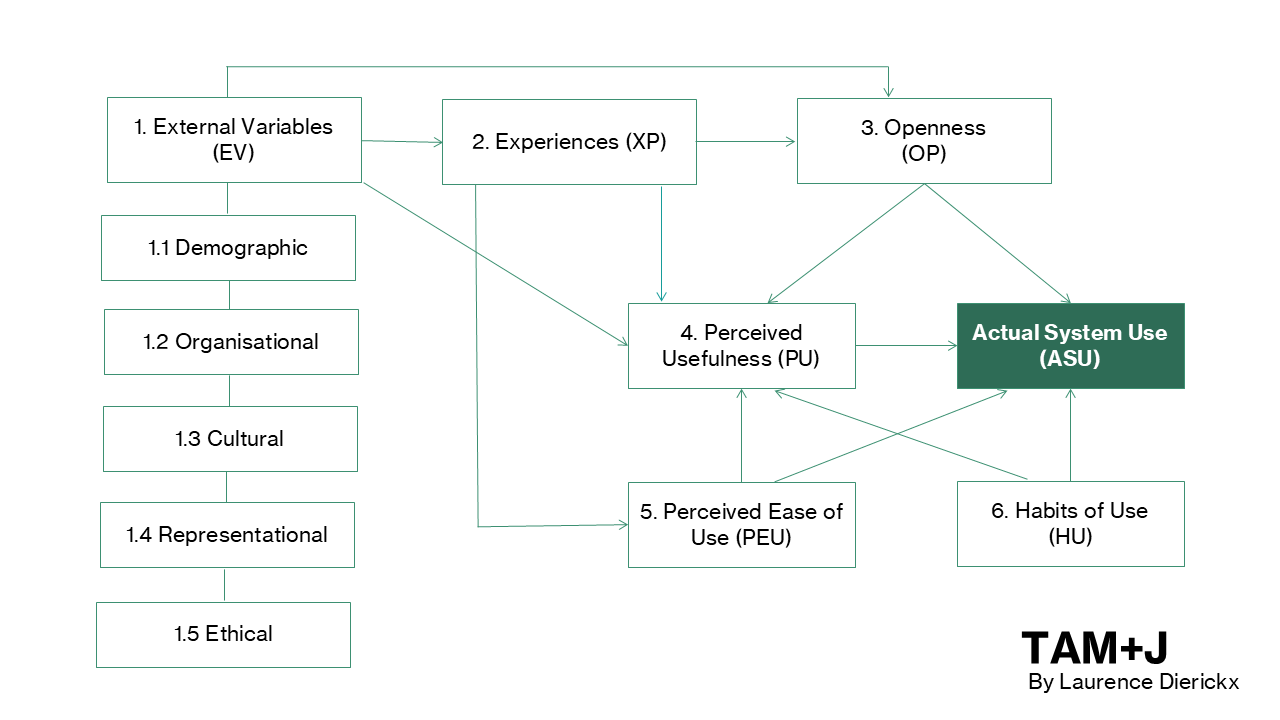

I can’t elaborate too much on last year’s study at the Digital Democracy Centre (University of Southern Denmark) on the use of generative AI tools to combat information disorders, as it is still being processed. But one key finding stands out: there is a noticeable shift in the way professionals engage with these technologies. Rather than trusting the tools – or the technology itself – fact-checkers are either leaning towards resilience, seeing AI as something that can and should be avoided, or showing a willingness to experiment with tools that live up to the latest hype. This divide reflects a broader tension in AI adoption: between scepticism and the drive to explore new possibilities, even when trust remains uncertain. This research is based on an adaptation of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which I have redesigned to better reflect the challenges of journalism.

The challenge of understanding and meeting users’ needs requires AI developers and newsroom managers to take a broad approach. Rather than simply offering new tools, they need to consider how these tools integrate with existing journalistic workflows, professional practices and ethics. The key to meaningful AI adoption isn’t just better technology – it’s better alignment with how journalists actually work.

References

- Dierickx, L., Sirén-Heikel, S., & Lindén, C. G. (2024). Outsourcing, augmenting, or complicating: The dynamics of AI in fact-checking practices in the Nordics. Emerging Media, 2(3), 449-473.

- Dierickx, L., Opdahl, A. L., Khan, S. A., Lindén, C. G., & Guerrero Rojas, D. C. (2024). A data-centric approach for ethical and trustworthy AI in journalism. Ethics and Information Technology, 26(4), 64.

- Dierickx, L., van Dalen, A., Opdahl, A. L., & Lindén, C. G. (2024). Striking the balance in using LLMs for fact-checking: A narrative literature review. In Multidisciplinary International Symposium on Disinformation in Open Online Media (pp. 1-15). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Dierickx, L., & Lindén, C. G. (2023). Journalism and fact-checking technologies: Understanding user needs. communication+ 1, 10(1).

- Dierickx, L. (2020). Journalists as end-users: Quality management principles applied to the design process of news automation. First Monday.

- Dierickx, L. (2020). The social construction of news automation and the user experience. Brazilian journalism research, 16(3), 432-457.

- Dierickx, L. (2017). News bot for the newsroom: How building data quality indicators can support journalistic projects relying on real-time open data. In Global Investigative Journalism Conference 2017 Academic Track.