What are the methodological challenges of studying media uses in crisis situations? This paper explores the question through the ontological, epistemological, and ethical aspects of a research project. Methods are also questioned, in terms of benefits and limitations.

Defining the scope

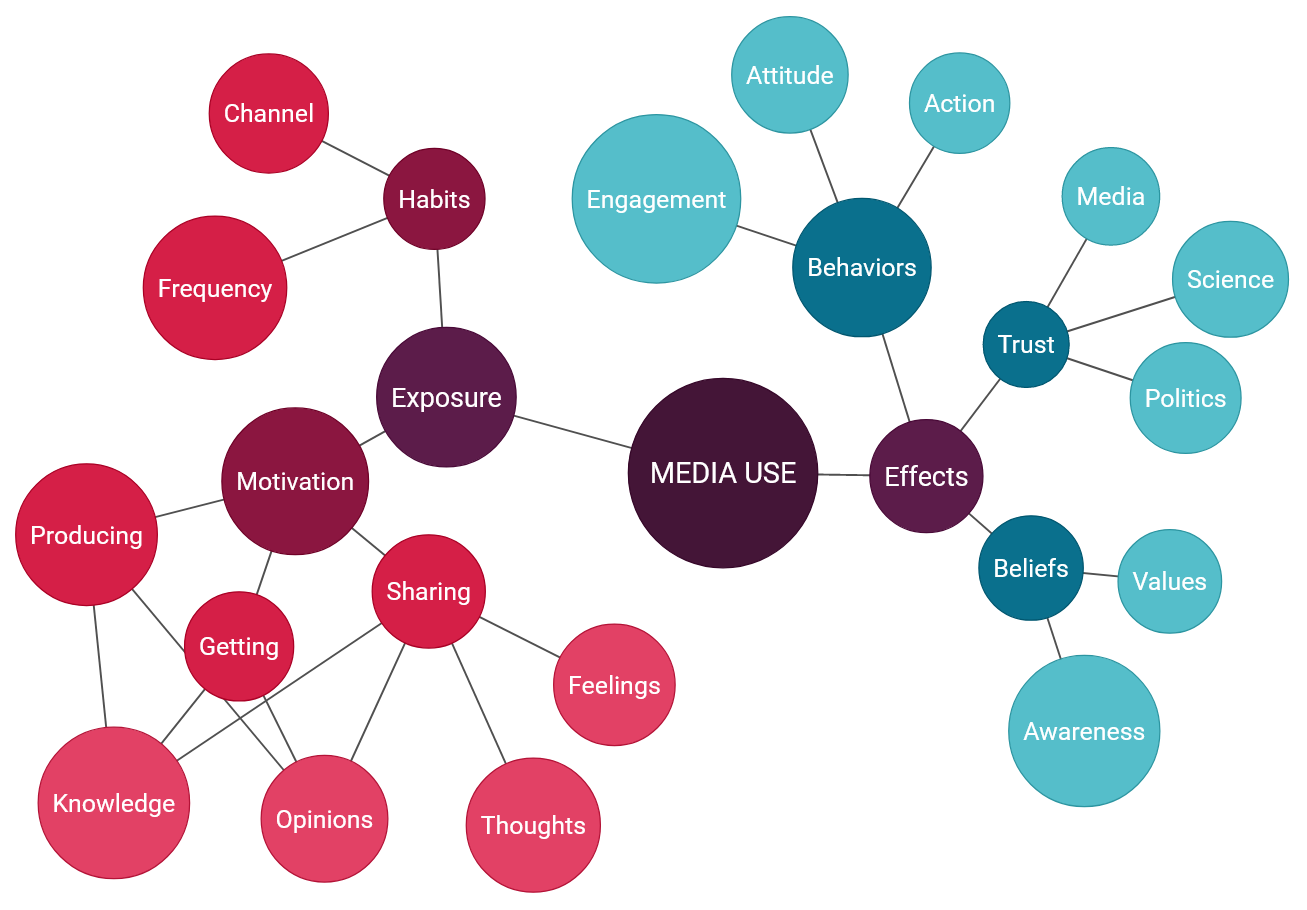

The characteristics of the mediatic ecosystem rely on its diversity, abundance, and hybridity. Mass media provide information but also comments and opinions from a wide range of authors of mediatic discourse. The study of media use can be related to the media effects, mainly focusing on audiences’ social, psychological, and behavioral impacts of media content. These effects can be direct or indirect, immediate, or deferred. They can be observed toward individuals or groups. The study of media use can also be related to the audience activity by focusing on the characteristics, motivations, and evolutions when consuming or using media.

These two approaches are intertwined (Zhao, 2009), so the measurement of how people are exposed to media content is essential for understanding media use and effects. In addition, media use cannot be detached from the context of use and the socio-economical or socio-cultural background of the user. Indeed, factors such as education, age, profession, or personal beliefs are intrinsically connected to media use.

Etymologically, the word “crisis” comes from the Greek “krisis” that means “judgment”, “decision”. The Chinese translation of the word “weiji” means both danger and opportunity. A crisis can be defined as a process of transformation where the old system can no longer be maintained (Venette, 2003). It is also described as a situation outside the usual framework of known incidents requiring urgent strategic decisions. Other definitions emphasize the unexpected nature of a disrupting problem. In sociology, a crisis is tackled as a collective situation characterized by contradictions and ruptures, significant tensions, and disagreements, making individuals and groups hesitant to take action (Freund, 1976).

The climate change phenomenon and the Covid-19 pandemic can be threatened as two distinct crises that share common patterns. In both cases, the crisis requires global and national answers. Its effects on the population are scalable and measurable, and they are likely to provoke feelings of anxiety and fear among the people. Although political responses may profoundly affect people’s habits, the consequences of climate change and the pandemic are expected to be very dramatic on human life and well-being. Scientific observations and discourses feed these political responses, and they enable to follow an ongoing process. Another common pattern is that these two crises are at the center of disputes and controversies, where facts and myths coexist. Because of their sounding-board power, mass media amplify these disputes and controversies.

New and old challenges

Researching media use in a crisis situation offers a wide range of possibilities, either in terms of exposure or effects. How are messages delivered and structured? What are the observed impacts on habits and motivation of use? Which channels are privileged? How do the contents affect beliefs, values, or behaviors? Do the users trust the information provided by traditional media? How does the crisis context influence online interactions? Are users active or passive? Do they show commitments or doubts? How do they react to misinformation? Do they build networks that comfort them in their beliefs? How does an individual use influence the perception or the representation of the crisis? Do users share their knowledge, and how?

This enumeration, which is far to be exhaustive, shows the potential when studying media use in crises situations. Therefore, it is essential to well define the scope of the research by tackling the question of what there is to know.

From an epistemological perspective, principles, fundamental concepts, and theories are essential to frame the methodology. The challenge is to describe and define not only general concepts but also new concepts such as “eco-anxiety”, “climate resilience”, “anti-vax”, or “covid skepticism”. What are their meanings and characteristics? Does the researcher interpret them from an empiric or an interpretative stand? How to classify and categorize concepts sharing common characteristics? Therefore, definitions can be expressed in theoretical, qualitative, or in subjective terms.

A crisis situation is an ongoing process. It implies that realities, attitudes, opinions, or behaviors are likely to evolve as the effects, and potential consequences of the crisis are discovered. These characteristics raise the question of the advisability of a longitudinal study, which results from monitoring a population or a phenomenon over time as a function of an initial event (Buchanan & Denyer, 2013). In addition, it is challenging to determine if people are affected by their media exposure and use or by the felt effects of a crisis situation in their day-to-day life. It must not be forgotten that the perception of reality results from a social and cultural construct (Berger & Luckmann, 1966).

Qualitative vs quantitative

A research methodology consists of a philosophical and theoretical approach to discovering knowledge. It is the basis of one or more methods, which can be defined as a procedure, a process, or a step that makes a research strategy operational. The methodology and methods must be consistent and appropriate regarding the aims of the research. They can also be combined, considering the research objectives.

Methods may also be used in a comparative perspective as a heuristic instrument to discover and explain relationships and possible causal links around phenomena (Brennen, 2017). For example, it can be used to compare attitudes, opinions, or behaviors between countries, which may be valuable in a time of crisis in terms of understanding and defining common patterns.

Qualitative research focuses on information that cannot be expressed as a number. Traditionally, the research in media studies uses qualitative interviews, focus groups, media history, textual analysis, ethnography, and participant observations. The aim is to provide a complete and detailed description of the research object to understand the wide range of possible relationships between media and society.

According to Tolich (2016), qualitative research aims to understand how people think about the world and how they act and behave. This approach requires researchers to understand phenomena based on discourse, actions, and documents, and how and why individuals interpret and ascribe meaning to what they say and do and to other aspects of the world they encounter.

In a qualitative approach, a research question aims to search for meaning and look for helpful ways to talk about experiences in a context that is likely to evolve in a crisis situation. The research process is here considered within relevant social practices. For instance, to understand how a given media use may influence environmental habits. It implies thinking about the researcher’s position, engagement, and critical distance with his field of investigation (Elias, 1983).

Such a research strategy is shaped by the personal perspective of the researcher and by direct and social interactions with the participants. Therefore, the challenge is connected to the interpretative nature of the observations and the active role of the researcher. Qualitative research is also challenging as it does not provide easy answers or simple truths. It can be controversial, contradictory, or ambiguous (Brennen, 2017).

Quantitative research focuses on data that can be quantified or expressed as a number, for instance, to classify characteristics or for building statistical models. Surveys, questionnaires, and content analysis are generally used to collect data.

A quantitative research strategy aims to discover facts about social phenomena. It allows us to picture a given situation at a T moment while we are living in a moving reality. It also refers to the myth of quantified objectivity (Espeland & Stevens, 2008). Nevertheless, numbers and their interpretation are likely to be as subjective as words. Moreover, data are about facts and not about explaining causes and consequences.

Machine learning for discovering new concepts

A quantitative approach can be used to provide predictions. For instance, about the psychosocial outcomes related to the mediatic messages about the pandemic. It can also provide insights. For example, through a language analysis to understand behavioral patterns related to a crisis situation. In addition, a quantitative approach may be hypothesis-driven or data-driven. In the first case, two variables must be defined: an independent one, related to the cause to measure, and a dependent one, related to the effects to measure (See Samuel et al., 2010; Coombs, 1998; Snelson, 2016; Liu et al. 2016; Schwartz & Ungar, 2015).

A data-driven approach is sequential and inductive. One of the assets of this approach is to discover new concepts, measure the prevalence of those concepts and assess causal effects to move away from a deductive social science to a more sequential, interactive, and inductive approach to inference (Molina & Garip, 2019). It allows dealing with the vast amount of data collected through social media platforms to shed light on people’s habits, opinions, and behaviors. Indeed, several research works highlighted the role of social platforms in crisis situations, either in the context of global warming or in the Covid-19 pandemic (Wu & Shen, 2021; Singh et al. 2020; Kligler-Vilenchik et al., 2020; Zhao & Zhou, 2021, Pérez-Escoda et al., 2020). However, when using such a research method, the challenge is to find the balance between a hypothesis-driven approach and a data-driven one (Denny & Spirling, 2018).

Benefits and limitations of the methods

Qualitative and quantitative research strategies are not characterized by a single approach, either in terms of a theoretical framework or methods. They can also be combined to provide complementary perspectives. From a theoretical point of view, the methodological apparatus can be related to the field of media studies but also be grounded in a transdisciplinary way. For instance, the sociological study of disasters has a long research tradition of investigating a wide range of social phenomena during and after natural, human-induced, and technological hazards events (Palen et al. 2007; Perry, 2018). Empirical qualitative methods are used mainly in this field, such as face-to-face interviews, gathering field documents, and capturing images. Indeed, crisis situations carry a lot of representations, either material or cognitive.

A wide range of methods can be used, each of them presenting benefits and limitations. No one is better than another: the choice of the methods comes from the research goals and objectives. However, it is important to remain aware of the benefits and limitations of the chosen ones. In addition, the validity and the reliability of the research method are two critical aspects to consider, so far as analysis and interpretations depend on these factors.

In qualitative research, ethnography is a tradition where the researcher observes particular settings and practices of people engaged in the experience. Although ethnographic methods may provide rich materials, they require time and a reflection of the researcher about his position, especially since that a crisis situation is also an emergency situation. In addition, the researcher may be personally affected by the crisis and the state of mind of the participants might be exacerbated because of dramatic recent events. The same issue appears in focus groups methods, where the role of the moderator is one of the success keys.

In questionnaires, there are risks related to the lack of comprehension or the lack of frankness of the respondent, who can have a hidden interest. Feelings and meanings are difficult to transmit through questionnaires, and they do not allow in-depth answers (Brennen, 2017). Such as in other qualitative methods, the cognitive frame to understand issues and outcomes of a crisis may be different from one respondent to another.

In quantitative analysis, data collected from social networks have many limitations. It involves the coding of thematic and categorical variables, which can also be qualitative. The representativity of the users is not granted compared with national populations, while the retrieving of data is faster. When moving to sentiment analysis, which relies on dictionaries that define the tone of a word, the risk is to get different results depending on the dictionary used. In addition, words are used in context and can be ambiguous or polysemic. Besides, are these lexicons really adapted for sentiment analysis in the context of crisis situations? Discover below the results of four sentiment analyzes carried out on a corpus of 5,000 tweets on #vaccination.

Machine learning techniques suppose big corpus, and the training phase must be improved to increase the algorithm accuracy. Indeed, in machine learning, there is not only one type of algorithm to perform a task, but they also all have their strengths and weaknesses, and their results can vary depending on changes in the data or the parameters (Lantz, 2015). It is to be said that quantitative methods allow discovering correlations but not causality. Moreover, content published on social networks may be volatile (Vasterman, 2018), and particularly changing in crisis periods.

Sample size and significance

Another challenge is related to the data source. Which population do we wish to observe? Do we consider that a limited number of cases or situations will be enough for description and analysis? Or do we consider that, due to the general and global aspects strongly connected to crisis situations, it requires a broader sample? Do we wish to focus on opinion leaders or everyday people?

The choice of the sample size is strongly connected to the research goals and objectives. The level of representativity of the participants is, therefore, important to define. They may be few but have the required characteristics for significance. Conversely, they may be numerous but without representing a given population, leading to bias in the sample. When data are gathered from social platforms, such as Twitter, content from protected accounts will not appear, and, therefore, the sample will not be complete. In addition, data gathered from online sources may be unreliable. It is also essential to keep in mind that bigger data are not always better data (Boyd and Crawford, 2012).

The data gathering may come from a variety of methods to confront and complete the results. This activity is not without carrying ethical implications.

Ethical considerations

Academic values encompass reliability and credibility. Reaching these standards requires methodological skills from the researcher to avoid unintended errors, and the respect of ethical standards commonly acknowledged. Whatever the research strategy is, participants must give their consent and be explicitly and accurately informed about all aspects of the research: purpose, methods, or possible outcomes. Participants also have to be informed about their right to withdraw at any time they wish. Their privacy and confidentiality must be protected and secured.

In qualitative research, the application of the right of privacy means the anonymization of the responses and being precautious as some responses may lead to the participant’s recognition.

In a quantitative research strategy, especially when it is data-driven, it is not obvious or easy to get the informed consent of the participant. The researcher must not forget the respect of privacy, especially since people may post content in a vulnerable state of mind in a crisis situation. In addition, people who publish content, comments, thoughts, or opinions on social media are not aware that their data may be collected and analyzed for research purposes (Eynon, 2017). The right to privacy is not only ethical: it also carries legal aspects.

To conclude, crisis situations take place in an ongoing and moving reality, where people are likely to be emotionally affected. It is not to be forgotten that science is about evidence and doubts and that media discourses and content are socially constructed and may evolve following the course of the crisis. That implies an ontological and epistemological position of the researcher when designing the research strategy. The challenges are also to fit the research purpose, questioning the methods in terms of benefits and limitations.

This process implies choices, and the researcher has to admit his commitment and subjectivity as a part of the process. It will enable us to think about the necessary and required critical distance. In all cases, the transparency of the process must be clearly framed regarding the intentions and motivations of the research and the decisions taken. All of these preoccupations are not specifically connected to crisis situations, but they appear as being crucial so far as it carries a lot of social and societal implications.

References

- Berger Peter, L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge.

- Boyd, D., & Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data: Provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon. Information, communication & society, 15(5), 662-679.

- Brennen, B. S. (2017). Qualitative research methods for media studies. routledge.

- Buchanan, D. A., & Denyer, D. (2013). Researching tomorrow’s crisis: methodological innovations and wider implications. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 205-224.

- Coombs, W. T. (1998). An analytic framework for crisis situations: Better responses from a better understanding of the situation. Journal of public relations research, 10(3), 177-191.

- Denny, M. J., & Spirling, A. (2018). Text preprocessing for unsupervised learning: Why it matters, when it misleads, and what to do about it. Political Analysis, 26(2), 168-189.

- Norbert, E. (1993). Engagement et distanciation. Paris, Fayard (1ère éd. 1983).

- Espeland, W. N., & Stevens, M. L. (2008). A sociology of quantification. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 49(3), 401-436.

- Eynon, R., Fry, J., & Schroeder, R. (2017). The ethics of online research. The SAGE handbook of online research methods, 2, 19-37.

- Freund, J. (1976). Sur deux catégories de la dynamique polémogène. Communications, 25(1), 101-112.

- Grimmer, J., Roberts, M. E., & Stewart, B. M. (2021). Machine Learning for Social Science: An Agnostic Approach. Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 395-419.

- Iphofen, R., & Tolich, M. (Eds.). (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research ethics. Sage.

- Kligler-Vilenchik, N., Stoltenberg, D., de Vries Kedem, M., Gur-Ze’ev, H., Waldherr, A., & Pfetsch, B. (2020). <? covid19?> Tweeting in the Time of Coronavirus: How Social Media Use and Academic Research Evolve during Times of Global Uncertainty. Social Media+ Society, 6(3).

- Lantz, B. (2019). Machine learning with R: Expert techniques for predictive modeling. Birmingham: Packt Publishing.

- Liu, B. F., Fraustino, J. D., & Jin, Y. (2016). Social media use during disasters: How information form and source influence intended behavioral responses. Communication Research, 43(5), 626-646.

- Molina, M., & Garip, F. (2019). Machine learning for sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 27-45.

- Palen, L., Vieweg, S., Sutton, J., Liu, S. B., & Hughes, A. (2007, October). Crisis informatics: Studying crisis in a networked world. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on E-Social Science (pp. 7-9).

- Pérez-Escoda, A., Jiménez-Narros, C., Perlado-Lamo-de-Espinosa, M., & Pedrero-Esteban, L. M. (2020). Social networks’ engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: health media vs. healthcare professionals. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(14), 5261.

- Perry, R. W. (2018). Defining disaster: An evolving concept. In Handbook of disaster research (pp. 3-22). Springer, Cham.

- Samuel, J., Ali, G. G., Rahman, M., Esawi, E., & Samuel, Y. (2020). Covid-19 public sentiment insights and machine learning for tweets classification. Information, 11(6), 314.

- Snelson, C. L. (2016). Qualitative and mixed methods social media research: A review of the literature. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1), 1609406915624574.

- Schwartz, H. A., & Ungar, L. H. (2015). Data-driven content analysis of social media: a systematic overview of automated methods. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 659(1), 78-94.

- Singh, S., Dixit, A., & Joshi, G. (2020). “Is compulsive social media use amid COVID-19 pandemic addictive behavior or coping mechanism?. Asian journal of psychiatry, 54, 102290.

- Vasterman, P. (2018). From Media Hype to Twitter Storm. Amsterdam University Press.

- Venette, S. J. (2003). Risk communication in a high-reliability organization: APHIS PPQ’s inclusion of risk in decision making. North Dakota State University.

- Wu, Y., & Shen, F. (2021). Exploring the impacts of media use and media trust on health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Journal of Health Psychology.

- Zhao, X. (2009). Media use and global warming perceptions: A snapshot of the reinforcing spirals. Communication Research, 36(5), 698-723.

- Zhao, N., & Zhou, G. (2021). COVID-19 stress and addictive social media use (SMU): Mediating role of active use and social media flow. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 85.